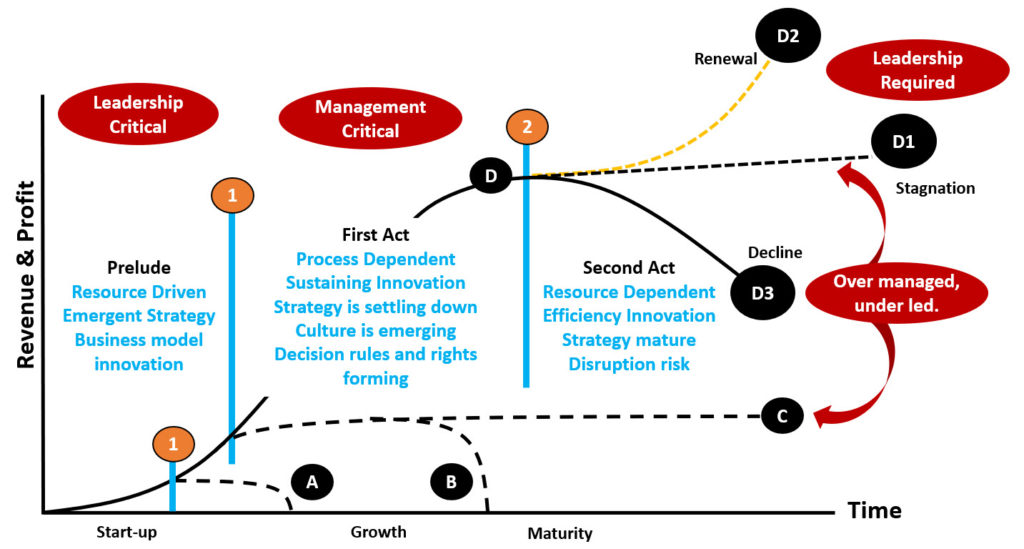

In business, as in life, there are three phases known variously as start-up, growth, and maturity/decline. The challenges that arise in each phase are different and call for different leadership and management responses.

Business Lifecycle Phases

In business, as in life, there are three phases known variously as start-up, growth, and maturity/decline. A much more colourful, but perfect, way of describing the phases is Start-up, Scale-up, and Screw-up.1

The Prelude

Every business experiences a lifecycle that consists of three parts. The start-up is the Prelude to the two main acts. It is the start of the business enterprise and is the period when the founder(s) is, or should be, seeking to confirm the business opportunity and validate a business model that will enable the business to scale. Four firm profiles emerge from this phase.

Firm Type A hits a brick wall almost immediately after coming out of the starting gate. These firms typically run out of cash and energy and rarely last more than 1-3 years. Michael Gerber suggests these founders suffer from an entrepreneurial seizure by seeking financial independence and reward in the belief they can do it better than the incumbents (usually their current boss) without really taking stock of the difficulties.

Firm Type B Secures a foothold in the industry but lacks a desire or ability to leverage talent and break through the first brick wall. These firms run out of steam and are acquired or close their doors. The reason for these failures is the founders underestimate how difficult it is to start and grow a business and they run out of resources, or motivation, but most importantly they fail to deliver enough value to enough prospective customers who are willing to pay a price that yields a profit margin. Another way of describing this is they have insufficient resources, no relevant experience, and no competitive strategy.

Firm Type C manages to get through the first brick wall after an initial burst of modest growth, but it then just cruises along in an uninspiring manner – sometimes called “the living dead.” Gets to maturity after initial growth spurt then just putters along blissfully unaware of the opportunity left at the starting gate. It has the same exit experience as firm B it just takes longer.

All three of these firm types are started by people who don’t have a big vision and/or drive to achieve much more than a job. The difference between them is the founders of Type A and B firms will get a job with someone else or exit the profession and Type C founders get to be self-employed but would have been better off as an employee. 90-98% of firms fall in the A-C categories.

Firm Type D are founded by people who have a growth aspiration. They will break through the first brick wall and grow solidly over time. Only about 2-5% of startups find their way to the pinnacle of this group of start-us.

The Prelude and the First Brick Wall

There are three types of start-up firms:

- Firms that enter an existing market and offer essentially the same value proposition as the incumbent firms by implementing essentially the same business model

- Firms that enter an existing market with a new business model

- Firms that seek to create a new market by offering a new customer value proposition

When a new firm enters an existing market with the same customer value proposition as the incumbents, the founder’s goal is to win market share. The challenge is winning enough customers quickly enough at a margin that gives the new entrant sufficient profit and cash flow fund growth. This is the first brick wall that all firms entering a market will face.

As a rule it’s quite easy to grab a share of an existing market that will give a new entrant about 20-30% of the revenue needed to get a solid foothold and start to make a living (note I said a “living” not a fortune or even a reasonable return on the capital, time, and risk involved). This revenue will come from friends, acquaintances, and from a small number of customers who are pissed off with their current service providers and/or because the new business is more convenient, offers lower prices, longer credit terms or some other “profit-eating” value proposition – it’s amazing how many people entering an industry believe the only thing customers want is lower prices.

For the most part, the quality of these new customers is terrible. They are the ones incumbent firms are quite happy to lose so in the worst case you end up with not enough customers of the type you need to build a great business and the firm either fails e.g. Firm Types A and B where the latter prefers a slow death than the former. Or they hang on like Firm Type C and achieve stagnant growth and putter along making a reasonable living in blissful ignorance of what they could achieve if they found a way to create and capture more value. These firms are “me too” businesses that replicate the business model of their average peers. It is a low risk, low return business plan and perhaps it shouldn’t even be called a plan, it’s just a behavior pattern.2

Irrespective of whether the new firm is attempting to create a new market or enter an existing market, in the Prelude phase the founders of Type D businesses are trying to figure out a strategy and related business model that will give them a competitive advantage. As is the case with all innovation, the development of a robust competitive strategy is an iterative process of trial and error at all levels of the organization and rarely more than 10% of initial deliberate strategies turn out to be the one that emerges. Strategic planning is a process not an event and the usual outcome of the process is often different to the initial idea.3

In the case of a new market entry, the competition is non-consumption; and in the case of an existing market, the competition is incumbent rival firms. In either case for the business to attract and retain quality clients and team members, the founders will need to come up with a new customer value proposition (and team member value proposition) and/or some other means of creating and delivering value that the industry has ignored.

Founders of businesses that seek to create a new market face a particularly challenging task because potential customers don’t even know they need or would want the product or service. The founder must therefore not only create the product but also create a market for it. If it works, the payoff can be enormous. Success usually follows many iterations of the business idea, but failure is the normal outcome. This is the ultimate act of entrepreneurial innovation.

A high level of leadership talent is called for to achieve serious growth in the First Act. The founder needs to be ambitious, smart, courageous, agile, resilient, and open-minded to be willing and able to pivot when things don’t work out exactly as expected which is what will happen most of the time. The key success here is how well the founder(s) has been able to adapt his or her management style and skill to lead the business into the serious growth phase – the first act.

Leadership is also critical in the Prelude phase because there is a small team where communication is informal and frequent, people are willing to work long hours and multi-task, and there is an air of excitement that’s highly motivational and fun for the “right” people. True leaders thrive in these collegiate circumstances but as we’ll see later, the leadership style that works brilliantly during the Prelude can be a problem later.

The first brick wall is likely to occur at different times for different firms depending on environmental conditions and the nature and size of the resource base of the start-up which includes people skills (including ability and reputation), available cash reserves, perhaps location, network contacts etc.

One of the most important weapons to break through into the First Act arena is being able to find and secure management talent. That is a game changer. Serendipity plays a part here in that if the founder is made of the “right stuff” and can find and attract talented people with a growth mindset and positive attitude, there’s a very good chance the business will blossom (refer to http://theconsultingaccountant.com/mindset-success-and-serendipity/ ). These people don’t need to be managed; they just need leadership.

On the other hand, what brings so many start-ups unstuck is making a bad hire because they got busy and, not wanting to risk too much of their hard-earned cash, bring on board the cheapest person they can find. This is always a disaster and if you combine that with shitty customers, few survive the set back or quickly join rank with the living dead.

The Prelude phase is resource-driven in the sense that what the business can and can’t do is limited by its available resources and, most importantly, by the way they are deployed. Provided there are sufficient resources (especially talented people) once the business model starts to work, rapid revenue and profit growth follows as the firm enters the First Act.

The First Act

The next phase in the lifecycle is a period of growth (sometimes rapid) which I call the First Act. Firm Type D makes it through the first brick wall and enters a period of strong revenue and profit growth although some firms fall off the wagon if they grow faster than their cash flow allows but most make it.

As the business grows, more people are required, and delegation and management become necessary. Communication can’t be as informal and frequent as it was during the Prelude. Leadership obviously remains critical, but the leader(s) must allocate a lot more time and effort to thinking about the future and much less time on product development, sales and marketing, and value delivery than they probably did in the Prelude phase. The collegiate style of leadership works less well in the high growth First Act phase.

Once the business concept has been validated, more management control is necessary simply because the organization is much more complex and requires direction although it’s important to manage the delicate balance between control and empowerment which plays a huge role in team motivation and engagement.

A critical feature of the First Act phase is the systemization of processes required to implement the firm’s strategy bearing in mind the strategy itself is still in the evolutionary phase so there will be tension between locking down an operating procedure with a documented system and the importance of continually questioning strategic efficacy. Systemization enables the business to do things efficiently that it struggled with before in part because the process is standardized and because there is clarity in relation to decision rules and decision rights which is essential for delegation to work. The systemization of operating procedures also makes hiring and training new team members much easier which improves productivity and engagement. Whereas, in the Prelude resources were the important ingredient, in the First Act management and processes are the keys.

One of the significant challenges in this phase is the increasing tension between control (manifested by systemization) and innovation. Innovation in this phase tends to focus on process improvement including product development, customer service improvement, sales and marketing effectiveness, performance measurement and success metrics, management development, and financial controls. This is called sustaining innovation because its purpose is to help the business better serve its customers while increasing its profit margin and market share. The objective is growth with process optimization.

For the most part, revenue growth in the First Act phase, particularly in the early stage, is organic and firms that are operationally superior and which can build their brand by differentiation, not just in name but by clearly having a deep understanding of, and ability to deliver, what their targeted customers value, are much more likely to experience organic growth.

However, in mature highly fragmented industries the industry output is a commodity and firms that seek to grow at a faster rate than the market will engage in mergers and acquisitions and the bigger they get M&A is the preferred growth tactic in the belief (hope) that it will be able to improve profitability from scale. Some firms develop a very high level of skill in being able to acquire and integrate other business that are a good fit with their strategic growth plan. Most however, don’t have these skills.

One salient observation I have had is that firms that grow predominantly through acquisition (i.e. revenue growth from acquisition being significantly greater than organic growth) tend not to create a sustainable competitive advantage that is reflected by improved profitability. Significant organic growth indicates the market’s acceptance of a firm’s value proposition and its ability to deliver on that promise by being able to command a price premium, attract new customers, sell more services to its customers, and/or by better customer retention.

The two reasons for using M&A as a growth engine is to access talent and quickly achieve scale but unless the acquirer has the capacity to properly integrate and retain the talent and is able to achieve profitable organic growth with its acquired customers, the return on the effort and cost of the acquisition is likely to be little more than the realization of a vanity goal than an economic one.

The big challenge with M&A growth is the difficulty with cultural and management integration. The culture of the organization represents its values, beliefs, and behavioral norms. During the Prelude, a culture starts to form and in the First Act, it solidifies around a set of behaviors and interpersonal relationships that seem to work and team members feel comfortable with. These are the visible and invisible values and norms that define “this is what we stand for, this is how we related to each other and our customers, and this is how we conduct our business”. Once a culture emerges it attracts and retains people who are comfortable with it and those who aren’t will leave. Those who stay, jealously protect it which might reflect humanity’s tribal roots that has helped us survive in a hostile environment over millennia.

If the founder has done a good leadership job, the early team members will have deeply shared values and beliefs which will be reflected in the firm’s vision and aspirational goals which in turn will be passed onto new hires. However, a good leadership job in this phase does not in itself mean the business will be successful, it simply means the founder has been able to create a uniform culture and if that’s compatible with the firm’s strategy and if implementing the strategy achieves competitive advantage, then success will inevitably follow. That is, culture is a necessary but not sufficient condition for success. It should also be mentioned that values and beliefs may not always be appropriate by some standards and yet the business may be successful at least for a while.

Different firms usually have different cultures and even though there may be substantial agreement between the groups there only needs to be a disconnect on some critical value or belief, not to mention a clash of egos, and you’re faced with a very hard row to hoe.4

Whereas the A, B and C Firm Types either totally fail or experience stagnant growth, Type D firms can become very profitable at least until they hit the second brick wall and are presented with three optional trajectories again.

The Second Brick Wall Through To The Second Act

“Whenever you see a successful business, someone once made a courageous decision.” This quote attributed to management guru Peter Drucker suggests that it’s curiosity and courage, not smarts, that creates Type D firms.

The First Act growth phase may last many years but without exception there will be a point of inflection where the rate of growth slows and starts to plateau. Immediately before the point of inflection the future looks very bright and everything seems to be working well. At this point hubris and complacency are at a high level but ironically this is precisely the time management should be thinking about the firm’s second act because at that point things start to change for the worst, often imperceptibly slowly.

This will happen for many reasons including poor management choices, disruptive product innovation from a new competitor, an emerging competitor’s disruptive business model innovation, a change in consumer tastes, market saturation resulting from over-capacity, loss of key team members, commoditization of the firm’s products leading to margin shrinkage. Hubris and complacency might replace innovation and energy, or simply the firm’s owners take their foot off the peddle because of changing aspirational or life goals and want to enjoy the cash that flows from a business that slows it growth and therefore does not allocate as much capital to fund innovation, growth and in the process possibly assume the risk of something going wrong.

The loss of key team members is one of the reasons for plateauing and is both a cause and a consequence of growth slowing. The leadership team that had the vision, the drive and ability to grow the business in the initial part of the First Act, typically find that the people with the skills needed to develop and manage the core processes (I’m intentionally switching between the word ‘leadership’ and ‘management’) are often not the type of people who have the skills to re-imagine the business after growth begins to stall.

When the C-Suite is dominated by managers who are more concerned with preserving what has been achieved, talented people who are looking for opportunity that can only come from growth will leave the organization. Oft times the founders will be okay with this because they’re enjoying their success and their aversion to risk has increased because they now have more to lose, and less energy, than they did at the start of their journey. There is a strong possibility those team members who leave becoming aggressive competitors of the mother ship!

Once the firm reaches a plateau, management is faced with two choice options.

- Pursue a D1 trajectory. Choose to maintain the present position and attempt to manage the business on a slow growth trajectory. Another option with this choice would be to sell the business and take some cash off the table and retire or continue working in some capacity. If a sale or merger is not possible this choice may end up as a D3 trajectory.

- Pursue a D2 trajectory. Adopt a start-up mentality again and develop a new aspirational goal and related strategic plan in which case the Second Act becomes the Prelude to the Third Act and the business is given a new lease on life.

The D1 Trajectory Choice

It is possible for industries to be populated exclusively by First Act and Second Act firms for decades on a D1 trajectory with firms positioned at various points along the path of that trajectory. Professional service industries are a good example. They fulfill a recurring customer need, they are self regulating, they apply a dominant but common business model, the industry enjoys some natural protection, and most firms are reasonably profitable (some very much so), and for the most part there is little, if any, innovation that is disruptive. There may, however, be a significant amount of sustaining innovation focused on operational efficiencies that enables firms to be more productive and even extend their service lines but these innovations diffuse rapidly and offer only temporary competitive advantage to early adopters if any at all.

These competitive forces lend themselves to favor a D1 trajectory choice for the owners of a firm that has developed over a fairly long period of time. The owners are likely to be satisfied with where the firm is positioned and simply seek to maintain that positioning with a modest growth profile supported by sustaining innovation. This is shown as a D1 trajectory and represents the majority of firms in mature industries.

The option to make this choice should be made at the point of inflection NOT at the plateau because a slowdown in the growth rate indicates that something has changed and if the firm’s growth rate is below the industry rate its competitive advantage and position is being eroded.

If the reason for this erosion is systemic it may be able to be fixed with some process or resourcing improvements. But if it’s the result of an industry disruption arising from changing customer tastes or needs (job-to-be-done), or from new value-creating technologies and related value propositions, etc. it’s likely that a new business model is required and if that’s the case a new business unit (and advisedly in a new legal entity) outside of the core business needs to be set up and run independently but concurrently with the core business with which it may even be competing.

When new technology innovations, including business model innovations, offer the prospect of a new value proposition most firms in an industry that are already doing well but would be able to do something with the innovation either ignore it or halfheartedly absorb it into their existing core business model and treat it as a sustaining innovation that supports its core service offering. According to Clayton Christensen, a world authority on disruptive innovation, the likelihood of that leading to a seriously successful implementation is zero because the day-to-day resource allocation decisions made at all levels within the firm will tend to draw it back to focusing on what it is already successfully doing. The accounting profession is exhibiting this right now in the way it’s floundering around with the introduction of advisory services which it sees as a natural line extension to its core (which is right for a minor piece of advisory), as long as it pursues that strategy it will never become a major player in the advisory space.5

The D3 Trajectory Demise

If one of these two choices is not taken it is highly likely that the firm will go into decline, which might happen anyway. It will happen if an attempt is made to renew the business via the D2 path which totally and irreversibly fails and it may happen if the stagnation D1 path is chosen and management finds it too hard to hold a steady state when everyone around you is intent on stealing your market share and your talent is walking out the door looking for more opportunities. Joseph Schumpeter called this phenomenon “creative destruction.”

In a later post I will talk about the role an advisor can and should play in each of the three phases of the business lifecycle.

NOTES:

- Vern Harnish, Scaling Up: How a Few Companies make it and why the Rest Don’t, Gazelles Inc., 2014, p.3

- I read somewhere that the goal of many people in the professions who start their own firms is to generate an income approximately equal to what they’re earning at the time they are thinking starting a firm. In other words, they do not seem to be motivate by the lure of financial rewards but seek independence and other non-financial rewards. My sense is that this also applies to business start-ups in general and it explains why most industries are populated by very average businesses. I offer this as an observation not a criticism but I believe it is one of the reasons the accounting profession is struggling to get traction in the advisory space. First, its own members are happy with the current business model and don’t feel the need, or are willing to invest the time and money, to pursue so-called “high value” work in the advisory space; and secondly, the average business person (read two thirds majority) is simply not interested in spending money on advice to take his/her business to another level.

- Clayton Christensen and Michael E. Raynor, The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth, Harvard Business School Press, 2003, pp214-216. And Rita McGrath & Ian MacMillan, “Discovery-Driven Planning”, Harvard Business Review, July-August, 1995. In a study of 400 Harvard Business School MBA alumni who had started a business after graduating of which 200 were very successful and 200 not so, the researcher found “93% of them said the strategy that led to success was completely different than the strategy they initially intended to pursue” as reported by Clayton Christensen in a Harvard Business School course Disruptive Strategy, 2019, Module 3.

- Culture plays a major role in the economic performance of businesses, for example see John P. Kotter and James L. Heskett, Corporate Culture and Performance, Free Press, 1992. For this reason if two cultures clash the impact on the operation of the whole can be serious and possibly catastrophic. Larger businesses can absorb smaller acquisitions quite easily and are therefore better able to manage the M&A process but when small firms merge the outcome is often bad for everyone and a significant amount of management time is wasted.

5. If you want to create a new market with new technology, you must set up a different business model in a different business unit, under the umbrella of, and with backing from, the current business. Alternatively, you can also look for a disruptive innovation as it is emerging, buy it and keep it separate from the core business. What that means is a manager needs to be able to look into the future and project at that point in time, what business model they need in order to succeed in that future because if you don’t prepare for it, when you need it the game will be over. The time to start looking is at the point of inflection during the First Act, that’s when your growth rate is still strong but growing more slowly, profit is high and cash flow is robust.

An example can be found in the retail industry.

In 1960 there were 316 traditional department stores in the US like Macy’s, Sears, Nordstrom, J. C. Penny, and a lesser known business Dayton-Hudson. Some were big some were regional and relatively small. Starting about 1962, the year in which Walmart was founded, low-end and discount stores started to appear in the retail space and of these Walmart emerged as a giant. Today only 8 of the original big department stores still exist. One of the most successful survivors was Dayton-Hudson.

In 1962 Dayton’s, John F. Geisse, could see an opportunity for an upscale discount store that was positioned between low-end discounters (Walmart hadn’t really hit the straps at the time) and up-market department stores. He realised things were happening in the market that would present an opportunity even though Dayton was strong and growing at the time with no pressing need to change. Geisse, opened a new store called Target while still operating their existing business under the Dayton-Hudson brand. The timing of Geisse’s decision is very important because circumstances were not forcing him to start Target so there was no pressure and because Dayton-Hudson was at the top of its game there were resources available to patiently invest in the Target initiative. This is what’s called a Dual Transformation – repositioning today’s business while creating the future – read the book the reference is below!

Target has continued to re-invent itself and today it now owns the retail space been the low end discounters and Walmart, in fact in recent times it has moved up a notch or two and sits between Walmart and the likes of Macy’s, JC Penney, and Kohls. Its success took it to the point where, in 2000 Dayton-Hudson Corporation changed its name to Target, the business that had effectively disrupted is parent from outside its core over the past 38 years.

The reason Target succeeded was that its management realized early that it needed a new business model with a different set of resources, processes, and profit model to support a new customer target (rising suburban middle class) with a new value proposition. Dayton operated two companies, one on the sustaining trajectory, one on the disruptive trajectory, and they managed that transfer from sustaining to disruptive by setting up a different business unit. But they were the only ones that have done that in the retail industry. There are a few in other industries. But in every case, they survived by setting up a different business unit to go after disruption.

One of the most important lessons from the Target experience is the realization that the best time to invest in growth (and especially disruptive growth) is when the core is strong and growing and appears to be at the top of its game with a bright positive outlook. See Mark W. Johnson, Reinvent Your Business Model: How to Seize the White Space for Transformative Growth, Harvard Business Review Press, 2018, also Anthony, Gilbert, and Johnson, Dual Transformation: How to Reposition Today’s Business While Creating the Future, HBR Press, 2017.

See Christensen & Raynor, op. cit. Chapters 7-10. And Clayton Christensen, HBX Course Material – Disruptive Strategy, Harvard Business School, 2019. To understand how Target developed over many years and why strategy development and implementation is a moving parade follow this link https://bit.ly/3ljgT9M

An interesting side benefit of reading the story of Target’s evolution is the role serendipity (luck) often plays in the founding and development of a business. But while luck remains in play, the story illustrates the most important function of leadership in strategy formulation and execution through experimentation. Great businesses are built by courageous people who are constantly surveying the environment and looking way ahead of today and then backing themselves.