In a recent post I referred to memo a business manager sent to his direct reports concerning the need to maintain margin even in tough times. I received a comment from a reader who wanted to know my views about pricing when you have surplus capacity in a industry with many competitors and low entry barriers. His view was that discounting makes sense in such a case especially if you have a lower cost structure. On the surface I would have to agree with that suggestion but I thought it would be useful to throw a few more thoughts around.

Pricing is both and art and a science but it’s the “science” bit that I’m going to refer to now. It is arguable that the pricing decision is the most important decision that any organization makes given its critical impact on revenue.

Other things being equal if you raise price the quantity of your products or services that customers are willing to buy will fall and vice versa when you drop your price. It’s important to note, however, that a decline in the physical volume of sales as a result of a price increase does not necessarily result is a decline in revenue. It might (and in fact often does!) result in an increase in revenue for the simple reason that people do not consider price to be the most important factor in their decision to purchase or, to put that another way, “all things” are NOT equal. Economists refer to this situation as inelastic demand and the more effectively you can “brand” your products or services and/or differentiate your business in other ways, the more pricing power you will have.

The big point is that you should always focus on pricing for profit not for revenue. If you have a lower cost structure than your competitors then you can drive home this competitive advantage by pursuing a low price strategy. If there are enough customers who consider price to be an important factor in their purchasing decision this would be a successful strategy–but note, the essential strategic focus is profit not revenue. Even though you have a cost leadership advantage you may also be able to differentiate in other ways that are valued by customers in which case you may choose to “bank” your cost advantage and let those other points of difference drive your volume.

But what if you do not have a cost leadership position? There may be times when you must consider lowering your prices. For example, suppose there is a downturn in the economy and a key customer demands a price drop; you probably don’t have a lot of choices unless you have significant supplier power to match your customer’s buying power. As long as the agreed price is greater than the variable costs associated with supplying the product or service you will achieve a positive contribution margin. This would be a rational pricing decision in the circumstances.

The above situation should be viewed as a special case because simply generating a positive contribution margin will not necessarily yield a net profit at the end of the day; this will only occur when your total contribution margin exceeds the total of your fixed costs. Any rational pricing decision needs to be cognizant of costs as well as pricing realities because although in the short term a loss may be tolerated as long as there is still a positive contribution margin, in the long term it will be necessary to raise prices or find some other way to reduce costs in order to return to profitability.

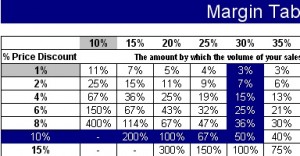

Remember, however, you may not have to drop your prices across the board (this should be an absolute last resort strategy) nor do you have to drop your prices for all of your customers. When you consider just how much additional physical sales volume you need to compensate for a price drop it’s easy to see why such a strategy will inevitably lead to lower profit. The table below shows that 50% more volume would be required to maintain your profitability if you were operating on a 30% Gross Profit and you were considering a price drop of just 10% – even if customers were that responsive to a 10% price cut it’s highly unlikely you would be able to accommodate a 50% volume increase with your existing capacity constraints. You can download this spreadsheet by clicking here.

There are other strategies you might consider. For example:

- Offer a range of product or service offerings with different price points ranging from high to low.

- Articulate very clearly what your value proposition is and price accordingly.

- Don’t voluntarily discount prices.

- Unbundle components of your offering.

- Bundle additional components into your offering (this might be done jointly with another business that deals with the same type of customers as you).

- Turn products into services.

- Turn services into products.

By far and away the most important strategy to implement in tough times is an unrelenting focus on your customer service protocols. For the most part, customers are not moved one way or the other by discounts. If you are attentive to your customers’ needs you should not have to discount to retain their loyalty. What’s most important is that you don’t fall into the trap of believing that in tough times revenue is king. Cash is king and cash flows from profit together with sound working capital management.