One of the most valuable services a business advisor can offer is Key Performance Indicator monitoring.

The quality of business outcomes (which we could define in terms of return on capital employed, return on shareholders’ funds, team turnover, growth in market share, earnings per share …. whatever you care to use as your objective function) will depend on the quality of decisions. The quality of decisions, in turn, depends on the quality of information on which they are based. When I refer to the quality of information I’m talking about its relevance to the critical success factors of the business, timing, accuracy and accessibility.

It also seems to me that a business that has better quality information to guide decisions taken by people who understand what they are looking at will have a clear competitive advantage over businesses that are run “by the seat of their managers’ pants.” The purpose of a KPI, in my view, is to get people to think about what’s going on. Albert Camus, a French Philosopher and Nobel Prize winner, said “life is the sum of all your choices”, I say, and so it is for business too. An understanding of how to use relevant KPIs will lead to better choices.

Net Profit is an example of a common KPI. Subject to the measurement rules embodied in GAAP this KPI reveals the financial consequence of past management decisions and operational activities given the economic environment that prevailed. In its simplest configuration, Net Profit is a residual being the difference between revenue, cost of sales and expenses. On its own it doesn’t tell us much other than the fact that revenues exceeded (or perhaps fell short of) total expenses. However, if it differs from expectation then management should want to know why.

If a loss has been incurred the questions management should ask are: Is this likely to continue? Why did the business lose money and what can we do to address the situation? For example, was it gross margin decline due to poor pricing and/or poor control over variable costs? Was it a physical sales volume issue? Are customers moving to competitors? Are customers’ buying patterns changing? Was it due to poor expense control? Was it due to a one-off extraordinary expense charge? The point I’m making here is that the measure of Net profit serves as a useful KPI but only if it is followed up by exploratory questions which require more information.

Net Profit becomes an even more useful KPI when looked at over time or in relation to other denominators or in relation to a target. For example, the trend in net profit is a useful indicator of what the future might hold if nothing changes. In this respect it serves as a high order key predictive indicator but potentially a dangerous one because it’s highly unlikely that “nothing” changes.

What’s far more revealing is an analysis of the factors that drive profitability. I’m talking about the impact of revenue (sales volume x price or average transaction value), gross profit margin, and expenses.

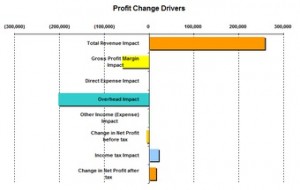

The Annual Business Performance Review generated by GamePlan provides an analysis of the impact that each of the net profit drivers have. This gives management some useful insights into the reasons for the change in profit from one year to the next.

Consider the analysis summarized in the above graph. The first point I’d make is this graph is a much more effective way to communicate what’s happening in a business that a table of numbers. But back to the discussion, there was a decrease in net profit before tax of $5,600. This was the net result from an increase in revenue of some $260,000 that was accompanied by a decline in GP% to yield a net increase in Gross Profit of $197,000 – the sterling sales effort was diluted by a reduction in margin margin. The decline in GP% (which means average selling prices did not keep pace with COGS) was accompanied, in this but not all cases, by a decline the average transaction value meaning that the number of transactions increased. This probably explains why Overheads have increased dramatically, so much so that the additional GP was more than consumed by additional overhead.

The profit drivers graph graph tells the story of what’s happened in the past year and like all good stories there should be something learned from it. It appears that the company drove sales hard due in part to aggressive pricing (reflected by a fall in GP%) and probably increased advertising expenses, perhaps higher sales commissions, more sales people etc. (there’s a need for further analysis of overheads). The net effect was virtually no change in net profit – a lot of effort for little result.

But there’s more, on yet even deeper analysis we discover that the GP% was just 1.16 percentage points below what it had been the previous year and 2.67 percentage points below the highest it had been in the past 5 years. Now these may appear to be small numbers but on revenues of $5,195,000 this decline in GP “cost” the business $60,000 and $139,000 respectively which represented more than 25% of its final net profit.

What’s also very important is the fact that if management had been aware of the “small” decline in GP% it may have been able to manage pricing more effectively. In fact a modest price increase of about 2% across the board would have preserved last year’s margin and added at least $60,000 to the bottom line. To achieve the highest GP% the price increase would have needed to be about 5%.

For the vast majority of small businesses the Income Statement is not being monitored regularly and rarely, if at all, are the sort of calculations I’ve talked about above been done. People in business for the most part do not understand either the logic or the algebra but what they do understand is:

Because you didn’t arrest the fall in your GP%, you have left $138,000 on the table. To avoid that outcome going forward all you needed to do is raise your prices by 5%

A popular cliché is the phrase “what you can measure you can manage.” Cliché though it is, in my experience it is a very useful idea. Time and time again, business people respond positively when you have a conversation about such things as: (1) there are just 4 ways to grow a business, (2) great results come from small changes, (3) when you monitor your business monthly you have 11 opportunities every year to get to where you want to be, (4) it’s the set of the sail that gets you to your destination not the intensity or direction of the wind, (5) expenses are the cost of resources used to generate your revenue, what return are you getting from them? (6) the most important non-financial KPI you need to be monitoring is the number of transactions (or some other activity metric)—from this an unbelievably rich source of information and probing questions will emerge.

Now one final point, most people would probably say that the mere act of measurement does not in itself change the object of measurement. I disagree. I have found that when a goal is put in place and it’s subject to a monitoring process the goal is achieved or exceeded more often than not. The key to this is not the goal, it is the regular monitoring and it comes back to the point I made earlier, if you intelligently review outcomes at least monthly then you’ll have multiple opportunities to “get it right.” If you give the goal attention, the activities you need to achieve the goal will be given attention. Simply having a target and casually comparing actuals with the target (if done at all) without giving attention to the causes and consequences is a waste of time.

Terrific point made here Ric. A recent personal experience wiht a SME client is a case in point. GP margin was budgeted at 40% (historical average) however from the get go (July) it was down (38%) and this trend continued for the next 2 months until Sept when it was 35% ($30,000 in lost GP).

Our recommendation that it be investigated fell on deaf ears. The drop in GP% remained entrenched at 35% until December when we again offered to investigate the reason. The client response was they would get their bookkeeper to do it (finally some agreement to act).

Result: a major supplier had increased prices by 20% 8 months earlier and nobody realised it!